By Lex Von Klark

In 2020, Massachusetts high school sophomore Calla Walsh made headlines for co-founding the Students for Markey campaign, a viral grassroots effort to drum up youth support for 74-year-old Democratic senator Ed Markey’s reelection campaign. In 2024, Walsh was indicted on felony charges for participating in a direct action against Elbit Systems of America, during which she climbed onto the roof of the building, damaged skylights and electrical systems, set off smoke bombs and sprayed red paint across the facade. Such extremely rapid radicalization – moving from creating memes for an aging progressive politician to engaging in industrial sabotage against Israel’s largest private weapons manufacturer in just under four years – is increasingly common in America, and leftist spaces are filled to the brim with people who have followed a similar path. What stands out about this wave of radicalization is not only its breakneck speed, but also its ideological end-point: across the country, young people disenchanted by liberalism’s limits have turned to a style of hyper-radical politics that Vladimir Lenin described as “Left doctrinairism” and Peter Camejo called “ultraleftism” (Lenin 1920, p. 74; Camejo 1970). Within the extremely loose network of organizations, media outlets, and online spaces that today comprise the Left, this ultraleftism has become almost hegemonic, shaping the political outlooks of tens of thousands of fresh radicals and determining the strategies chosen by movements as varied as the Palestinian solidarity encampments and the Stop Cop City campaign.

In order to understand what ultraleftism is and discover why it has become so popular today, two classical analyses of the subject from wildly different time periods will be put into conversation with each other. By comparing Lenin’s ‘Left-Wing’ Communism: An Infantile Disorder and Camejo’s Liberalism, Ultraleftism or Mass Action, we can discern the core characteristics of ultraleft politics and learn what kinds of conditions lead to its rise. As socialists who seek to win the working class over to anticapitalist politics, understanding ultraleftism is essential for comprehending the present state of our movement, recognizing its limits, and organizing ourselves to surpass it. Only by openly critiquing modern Left doctrinairism and adapting ourselves to the material conditions that drive it can our movement become a unified force oriented towards the broad masses of the working class who actually have the power to win change.

Lenin

Lenin wrote ‘Left-Wing’ Communism: An Infantile Disorder in 1920, amidst a political context entirely unlike our own. The revolutionary social-democratic movement, organized domestically within powerful mass parties such as the Social Democratic Party of Germany and connected internationally through the Second International, had just shattered following the outbreak of World War I. Abandoning their professed commitment to revolutionary internationalism, the leaders of the European social democratic parties publicly pledged their support for their home countries’ war efforts, embracing nationalist chauvinism at the expense of international working-class unity and functionally destroying the Second International. This stunning betrayal was followed by further opportunist depravity: the Social Democratic Party of Germany, previously the paragon of the revolutionary movement, co-opted the 1918 German revolution and worked vigorously to suppress and destroy the revolutionary forces that sought to establish a council-based workers’ republic, even going so far as to empower proto-Nazi paramilitaries to massacre the socialist revolutionaries (Hoffrogge 2015, p. 123). Due to this wave of opportunism and nationalism that overtook the parties of the Second International, Lenin writes that “opportunism, which in 1914 definitely grew into social-chauvinism…was the principal enemy of Bolshevism in the working class movement” (Lenin 1920, p. 17). There was another enemy within the working class movement that Bolshevism faced, however, one which grew largely in response to the betrayal of the Second International: “petty-bourgeois revolutionariness” (ibid).

Also described by Lenin as “Left doctrinairism” and “‘Left-wing’ Communism”, “petty-bourgeois revolutionariness” was his central subject of analysis and criticism in ‘Left-Wing’ Communism: An Infantile Disorder. Rather than referring to a cohesive, singular ideology, Left doctrinairism was a broad label that included a wide array of organizations and beliefs including the German “Communist Labor Party”, the British “Workers’ Socialist Federation and the Socialist Labor Party”, the Italian “‘Communist-Boycottists’”, and the American “Industrial Workers of the World and the anarcho-syndicalist trends” (ibid, p. 85, 60, 48, 72). What united these disparate groups was that they “have mistaken their desire, their ideological-political attitude, for actual fact” and in so doing failed to “conduct themselves as the party of the class, as the party of the masses” (ibid, p. 41, 42). Instead of working with “the human material bequeathed to us by capitalism”, that is to say, strategically adapting to present conditions in order to win over the masses, the Left doctrinaires hurled revolutionary-sounding slogans and substituted ideological dogma for material analysis (ibid, p. 34). By determining policy only according to “mere desires and views, and by the degree of class consciousness and readiness for battle of only one group or party”, the Left doctrinaires severed themselves from the masses who had not yet ‘caught up’ to their level of radicalization (ibid, p. 62).

One such policy embraced widely amongst the Left doctrinaires was the “repudiation of the necessity of participating in the reactionary bourgeois parliaments and the reactionary trade unions” (ibid, p. 55). Justifiably terrified of repeating the mistakes of opportunism, the Left doctrinaires attempted to cut themselves off from reactionary institutions like parliament & the trade unions in favor of creating their own “absolutely brand-new, immaculate” unions and workers’ councils which would theoretically be free of bourgeois influence (ibid, p. 34). For Lenin, since the vast majority of the working class in the West still followed their parliaments and trade unions, such a policy of voluntary separation amounted to “regard[ing] what is obsolete for us as being obsolete for the class, as being obsolete for the masses” (ibid, p. 42). “As long as you are unable to disperse the bourgeois parliament and every other type of reactionary institution,” wrote Lenin, “you must work inside them, precisely because there you will still find workers…otherwise you risk becoming mere babblers” (ibid). Rather than abandoning the backwards elements of the working class and rushing ahead with one’s own radical beliefs, “the whole task of the Communists is to be able to convince the backward elements, to work among them, and not to fence themselves off from them by artificial and childishly ‘Left’ slogans” (ibid, p. 38).

It must be emphasized that Lenin’s opposition to Left doctrinairism was not based on them having incorrect principles, but rather due to their failure to think strategically. Indeed, Lenin sympathized with their hatred of opportunism: “It [hatred of parliament] is quite comprehensible, for it is difficult to imagine anything more vile, abominable and treacherous than the behavior of the vast majority of the Socialist…parliamentary deputies during and after the war” (ibid, p. 46). The problem with Left doctrinairism was that not that they opposed opportunism, but rather that in attempting to distance themselves from opportunism, they inadvertently made “the same mistake, only the other way round”; where Right doctrinairism failed because it “persisted in recognizing only the old forms…[and] did not perceive the new content”, “Left doctrinairism persists in the unconditional repudiation of certain old forms and fails to see that the new content is forcing its way through…that it is our duty as Communists to master all forms, to learn how with the maximum rapidity to supplement one form with another…and to adapt our tactics to every such change not called forth by our class, or by our efforts” (ibid, p. 83, 84). Where Right doctrinaires clung to the “old forms” of parliament and reactionary trade unions long after they have been rendered useless in the struggle, Left doctrinaires preemptively rejected those “old forms” long before they have actually been rendered superfluous, thus damning themselves to irrelevance. It was, according to Lenin, the job of Communists to continue working within those old forms as long as they remain relevant, that is to say, as long as they still commanded the attention & loyalty of large swaths of the working class.

Lenin viewed Left doctrinairism as a reaction to opportunism, arguing that the two often historically went hand-in-hand: “Anarchism was often a sort of punishment for the opportunist sins of the working class movement. The two monstrosities were mutually complementary” (ibid, p. 18). Where opportunism grew, Left doctrinairism would follow, as members of the European social democratic parties who felt betrayed by their chauvinist leaders adopted increasingly ‘revolutionary’ stances meant to distance themselves as much as possible from opportunism. These newly radicalized Left doctrinaires were, according to Lenin, typically “young Communists, or…rank-and-file workers who are only just beginning to accept communism”, and he repeatedly characterizes them as “immature and inexperienced” (ibid, p. 61). In terms of popularity, Left doctrinairism was still relatively small compared to other trends like opportunism or Bolshevism. “The mistake of Left doctrinairism in Communism is at present a thousand times less dangerous and less significant than the mistake of Right doctrinairism (i.e., social-chauvinism and Kautskyism),” wrote Lenin, “but, after all, that is only due to the fact that Left Communism is a very young trend, that it is only just coming into being” (ibid, p. 83). Beyond just being a “very young trend”, Left doctrinairism’s popularity was also hampered by the visible success of Bolshevik-style mass-organizing, which offered a viable alternative to both chauvinist opportunism and dogmatic ‘Left-wing’ communism. In time, however, left doctrinairism would grow to pose a much bigger threat to the organized left – but Lenin, who died four years after writing ‘Left-Wing’ Communism, never lived to see it.

Camejo

While Lenin examined Left-doctrinairism at a moment when it was “a thousand times less dangerous and less significant than…Right doctrinairism”, Peter Camejo analyzed it at a time when it made up “a much larger proportion of those who call themselves radicals or socialists” (ibid, Camejo 1970). Speaking before a June 1970 meeting of the Young Socialist Alliance, the youth wing of the Trotskyist Socialist Workers Party (SWP), Camejo considered the state of the anti-Vietnam war movement and critiqued what he labeled the “liberal” and “utraleft” perspectives, advocating instead for an “independent mass action” orientation (ibid). Himself a leading member of the SWP and an active organizer within the antiwar movement, Camejo sought to respond to criticisms of the SWP “being raised within the radical movement”, and began by providing a broad overview of the “relationship of forces” within the country (ibid).

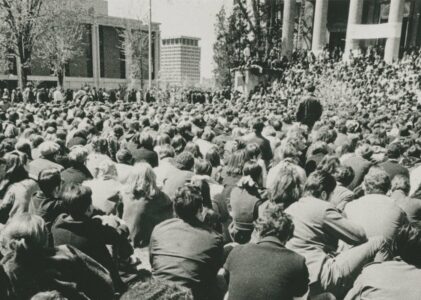

The anti-war movement was at a crossroads. Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), the largest of the student anti-war organizations, had just imploded the year before at a catastrophic national convention defined by hard-line sectarianism. SDS’s collapse was itself both a cause and an effect of ultraleftism’s growth, as the organization’s destruction at the hands of disciplined cadre groups like the Progressive Labor Party led to the proliferation of even smaller, more radical sects such as Revolutionary Youth Movement II and the Weather Underground (Young 2018). Despite the destruction of one of its leading organizations, the student antiwar movement continued to grow: in May of 1970, the month before Camejo gave his speech, over 4 million students from nearly 900 campuses across the country went on strike to protest against the war (Early 2020). Incited by Nixon’s decision to invade Cambodia in late April, the walkouts exploded in popularity after the Ohio National Guard killed four protestors at Kent State University, and “millions of students, many of whom had never participated in the antiwar movement before, took part” (Miller 2020). On campuses from coast to coast, huge supermajorities of students went on strike, and Camejo himself estimated that “virtually 98 per cent of the student body is striking in many schools and three-quarters of them are showing up for the mass strike meetings” (Camejo 1970). Unlike previous nationwide protests against the Vietnam War, the May student strike was spontaneous and uncoordinated, spreading without the backing of any major anti-war organizations. Even without any large-scale planning, however, the student strike was still so popular and disruptive as to make even Henry Kissinger feel that the “very fabric of government was falling apart” (Miller 2020).

By the time Camejo appeared before the YSA meeting on June 14th, the May strike was largely over, as students had left their campuses to return home for summer break. But while the strike itself had come to an end, the radical energies it had unleashed could not so easily be dispersed: by exposing millions of students, many for the first time in their lives, to the power of collective action and the brutality of state repression, the strike radicalized huge numbers of students on issues extending far beyond just the Vietnam war. “A good example of this process [of radicalization] was during the May strike movement,” Camejo said, as “many students who helped build the antiwar universities became really aware for the first time of the repression against the Black Panthers and raised concrete demands to free the jailed Panthers” (Camejo 1970). This spontaneous explosion of youth radicalization presented an unprecedented opportunity for the antiwar movement, but without a unified national organization such as SDS to provide coordination and planning, the question remained of how exactly the scattered remains of the organized left should take advantage of the moment. Camejo’s speech sought to answer this question by identifying and choosing between the three strategic “orientations that are being presented to us for what to do next”: liberalism, ultraleftism, and independent mass action (ibid).

The three orientations identified by Camejo are theories of change, each with their own distinct set of assumptions about who holds power in society and how demands can be won. For liberals, it is the elites who hold all of the power, and winning change depends on “finding a politician who’s responsive” (ibid). Rather than looking to the masses, liberals “look directly to the ruling class and try to affect the course of events by relating to any differences within the ruling class” (ibid). They do this because “they have confidence that the system basically works”, and that “the only problem is to find members of the ruling class who are responsive” (ibid). This liberal perspective “represents the ideology of the overwhelming majority of the student movement”, and while “most students on the campus are suspicious because of the war…and because of the radicalization that’s affected them”, “nevertheless, they’re still willing to give the politicians…another chance” (ibid).

Ultraleftism, the second orientation identified by Camejo, develops out of liberalism: “an ultraleft is a liberal that has gone through an evolution” (ibid). Similar to Lenin’s description of Left-doctrinairism as a response to the failures of opportunism, Camejo viewed ultraleftism as a reaction to the limits of liberalism. “In the beginning when the antiwar movement first started there were very few ultraleftists”, wrote Camejo, “most of the ultraleftist leaders of today were people who were organizing legal, peaceful demonstrations back around 1965” (ibid). Following their liberal worldview, these demonstrators initially believed “that the ruling class is basically responsive” and would listen to their protests, but they quickly “noticed something was wrong. The ruling class was not being responsive. Not only that, they understood for the first time that the US was literally massacring the Vietnamese people” (ibid). For these liberals who had such a strong faith in their ruling class and its institutions, these revelations were as traumatic as finding “out that your father was really the Boston Strangler”, and caused many to reevaluate their conviction that “the system basically works” (ibid). Where previously they saw the ruling elite as benevolent and responsive, the liberal-ultraleftists now viewed them as “wild maniacs and butchers” – crucially, however, they still believed “that the ruling class is all-powerful” (ibid). This meant that rather than completely breaking with liberalism’s logic, the ultraleftists merely inverted it, maintaining the same basic structure (“the ruling class is all-powerful…”) while swapping liberalism’s faith for ultraleftism’s pessimism. Hence, Camejo describes them as “ultraleft-upside-down-liberals” (ibid).

Given this, ultraleftism’s set of assumptions about who holds power in society and how demands can be won are as follows: just as in liberalism, the elites hold all of the power, but unlike liberalism, the elites are not responsive, and winning change cannot be accomplished by peacefully appealing to them. Instead, the elites must be forced to listen through radical acts of disruption, as “the way to get them to pay attention is to go out and break some windows and use violence” (ibid). Since ultraleftism shares liberalism’s lack of faith in the power of the masses, “they think it is enough for them to leave the system themselves, small groups of people carrying out direct confrontations”, and they prioritize minoritarian actions that only move extremely small already-radicalized cells to action. Indeed, “this is the key thing to understand about the ultraleftists. The actions they propose are not aimed at the American people; they’re aimed at those who have already radicalized. They know beforehand that masses of people won’t respond to the tactics they propose” (ibid). One of the main ways ultraleftists artificially separate themselves from the masses is by demanding that participants in their movements agree with them on every conceivable issue, including those issues not immediately related to the subject at hand. Camejo illustrates this point using the hypothetical example of a woman who supports abortion rights but “still has illusions about the war in Vietnam, still supports Nixon” trying to join a demonstration for free abortions on demand. For ultraleftists, allowing this woman to join their abortion demonstration would “taint ourselves”, so they decry her by saying “You’re an imperialist pig!…You can’t go on this demonstration. Keep away from us. We understand these things — we’re the elite” (ibid). Camejo contrasts this elite, minoritarian response with “the…strategy which is used by a union when it carries out a strike”, wherein union members focus in on “certain demands”, rather than asking each worker “‘Why don’t we also take a stand on the Arab-Israeli conflict? Or on housing, or on the last bill passed in Congress?’ as a prerequisite to participate in the strike” (ibid). This emphasis on maximizing mass participation by focusing on a clear set of popular demands, rather than attempting to address “everything at once” with an already-radicalized core, is what Camejo refers to as independent mass action.

Independent mass action is Camejo’s third strategic orientation, and it aims to not merely invert liberalism like ultraleftism does, but to actually fundamentally break with liberalism’s core assumptions about power and politics. Where liberals and ultraleftists see power as entirely concentrated in the hands of the ruling class, mass action socialists understand power as a constant struggle in which the huge population of working people holds immense leverage. Given this, the way to win change is not to appeal to the ruling class through peaceful demonstrations or radical riots, but rather to move the masses themselves into action: “We’re not interested in moving 20 or 200 or several hundred community organizers to engage in some sort of civil disobedience, window trashing, or whatever”, argued Camejo, “We say that is a dead end, because it doesn’t relate to the power that can stop the war — the masses” (ibid). Strategically speaking, mass action means “trying to build movements which reach out and bring masses into motion on issues where they are willing to struggle against policies of the ruling class, and through their involvement in action, deepen their understanding of those issues” (ibid). By meeting the masses where they are at and organizing around issues they already care about, rather than leaping ahead with super-radical actions that alienate most people, the masses can be moved into struggle and radicalized in the process.

At the time of Camejo’s speech, ultraleftism represented “a small section of the student movement, but a much larger proportion of those who call themselves radicals or socialists” (ibid). This was primarily because the student movement, at that time embodied in the May strike, had expanded beyond the ranks of the already-radicalized and grown to include huge supermajorities of regular students who were just beginning to become politicized. The spontaneous and uncoordinated nature of the strike indicates that this expansion of participation was not due to any effective mass organizing on the part of the radicals, but rather due to the immense popularity of the anti-war cause at the time among students and the broader population. Indeed, unlike the May strike which had organically expanded to include broad masses of students who were not already radicals, the left at the time was dominated by ultraleftism and had little mass appeal. The destruction of SDS and the ensuing proliferation of tiny, ineffective Maoist-third-worldist sects (including the terroristic Weather Underground) were both consequences and causes of the spread of ultraleftism, and the rejection of mass organizing inherent to that orientation ultimately doomed the radical left to irrelevance, powerlessness, and disintegration for nearly half a century.

A Unified Theory of Ultraleftism

Though articulated on opposite sides of the world nearly half a century apart, Lenin’s description of left-doctrinairism and Camejo’s description of ultraleftism so closely parallel one another that it seems more than likely that they were describing the same phenomenon. Based on their analyses, I propose the following four central characteristics of ultraleftism across time:

I. Ultraleftism primarily develops as a reaction to the limits of center-left politics.

Lenin and Camejo both viewed ultraleftism as a response to the failures of center-left politics. For Lenin, this took the form of a reaction to opportunism: “Anarchism was often a sort of punishment for the opportunist sins of the working class movement” (Lenin 1920, p. 18). For Camejo, it took the form of a reaction to liberalism: “an ultraleft is a liberal that has gone through an evolution” (Camejo 1970). For both, it was the inability of center-leftism to win its demands (either uniting the international working class for revolution, in Lenin’s case, or bringing the Vietnam war to an end, in Camejo’s case) that caused many people to become ultraleftists, as they sought to radically repudiate the politics that had failed them so dramatically.

II. Ultraleftism inverts center-left thinking without breaking with its fundamental structure of thought.

In attempting to reject their former center-left beliefs, however, ultraleftists inadvertently mirror many of center-leftism’s core assumptions about power and strategy; or, as Lenin put it, they make “the same mistake, only the other way round” (Lenin 1920, p. 84). Camejo similarly views ultraleftism as a kind of inverted center-leftism, describing ultraleftists as “ultraleft-upside-down-liberals” who still hold onto liberalism’s belief that the elites hold all of the power (Camejo 1970). The reason why ultraleftists merely invert center-leftism is because they primarily define themselves as anti-center-leftists, thereby ensuring that all of their positions are simply upside-down versions of their former strategic orientation. Like a mirror shows a reversed image of an object without fundamentally altering the characteristics of that object, ultraleftism reverses liberalism without changing its core assumptions. This sort of extreme negative polarization leaves unchallenged the center-left elite model of power, and ultimately causes ultraleftists to pursue elite-oriented strategies.

III. Ultraleftism rejects mass organizing in favor of minoritarian strategies that only mobilize the already-radicalized.

The worst sin of ultraleftism, and the reason why it is insufficient to win real change in society, is identified by both Lenin and Camejo as its rejection of mass organizing. By embracing hyper-radical positions and rejecting working in reactionary institutions like parliament or trade unions, ultraleftists “fence themselves off from them [the masses] by artificial and childishly ‘Left’ slogans” (Lenin 1920, p. 38). Instead of meeting the masses where they are at by strategically participating in reactionary institutions or running campaigns based on widely popular issues, ultraleftists abstain from parliament and organize minoritarian actions that only appeal to the already-radicalized. As for why exactly they do this, Lenin and Camejo have divergent explanations. For Lenin, ultraleftists fail to organize the masses because they “have mistaken their desire, their ideological-political attitude, for actual fact”, and in doing so incorrectly assume that “the degree of class consciousness and readiness for battle of only one group or party” is representative of the state of the masses as a whole (ibid, p. 62). Since they believe the masses are just as radical as they are, Lenin argues, the ultraleftists pursue extremely radical tactics that in practice actually alienate the masses. For Camejo, ultraleftists fail to organize the masses because they reject the masses as a force capable of winning change in society: “they [ultraleftists] had no confidence in the masses as an independent force that could stop the ruling class”, and indeed “they have not only given up on the masses but really have contempt for them” (Camejo 1970). This difference in attitude towards the masses between the ultraleftists of Lenin’s time and the ultraleftists of Camejo’s time seems primarily to be a result of their wildly different historical contexts. When Lenin wrote “Left-Wing Communism”, the kind of mass politics pioneered by “German revolutionary Social-Democracy” and the Bolsheviks was widely recognized as the paragon of left-wing organizing due to its unprecedented ability to build social power, and, in the case of the Bolsheviks, actually win a revolution. So hegemonic was the Bolshevik strategy of mass organizing at the time that even the ultraleftists sought to discursively emulate it, using the language of mass organizing without actually adopting its tactics, or as Lenin says “the ‘Left’ Communists have a great deal to say in praise of us Bolsheviks. One sometimes feels like telling them to praise us less and to try to get a better knowledge of the Bolsheviks’ tactics” (Lenin 1920, p. 42). In contrast, when Camejo gave his Liberalism, Ultraleftism or Mass Action speech, there was no visible, successful current of mass organizing within the American left for others to draw inspiration from or seek to emulate. Instead, the left was dominated by tiny ultraradical sectarian groups who viewed the American masses of the 1970s as hopelessly reactionary labor aristocrats, an image which was only reinforced by events such as the May 20th demonstration in favor of the Vietnam War by trade union construction workers in New York City (Camejo 1970). That ultraleftism can either discursively embrace or denounce the masses without challenging its fundamental inability to pursue mass politics demonstrates the ideological flexibility of the ultraleft orientation, which can mobilize a diverse range of political signifiers in service of its strategic outlook.

IV. Ultraleftism is a strategic orientation which can manifest as a wide variety of ideologies.

Rather than being wedded to any particular ideology or political tradition, ultraleftism has taken a diverse array of forms throughout its history. In Lenin’s time, it manifested primarily as “anarchism”, “syndicalist trends”, “petty-bourgeois revolutionism”, and “Left-Communism” (Lenin 1920, p. 17, 72, 21). In Camejo’s time, ultraleftism predominantly took the form of Mao Zedong-inspired “Thirld World Marxism”, which itself was internally divided among a large number of hardline microsects such as the Progressive Labor Party, Revolutionary Youth Movement II, the Communist Party (Marxist-Leninist), the Revolutionary Communist Party, and, most infamously, the Weathermen (Young 2018). While some ideologies definitionally tend towards ultraleftism because of their inherently minoritarian tactics or theories of change, such as anarchism and Maoist third-worldism, others can be mobilized in service of either ultraleftism or mass politics depending on which elements of the ideology are emphasized, as is the case with Leninism. Ultimately, the specific forms taken by ultraleftism within a given time period are a result of the historical context and contemporary political topography, which present newly radicalized ultraleftists with a set of ideological alternatives to their previously center-left politics. Which of these alternatives the ultraleftists embrace is determined by which one seems to most completely invert their former center-leftism, leading ultraleftists to typically pick the most radical-sounding option.

Now that we have uncovered the core characteristics of ultraleftism identified by Lenin and Camejo’s analyses, we can turn to considering our own present political moment and the position of ultraleftism within it.

Ultraleftism Today

For most of the fifty-four years since Camejo gave his speech, the American left has only grown more disorganized, splintered, and isolated. The failure of the New Communist Movement of the ‘70s and ‘80s to overcome its sectarian impulses and generate mass appeal meant that by the turn of the century, the organized left was basically non-existent outside of a handful of tiny socialist sects, anarchist groups, and ineffective NGOs. This was clearly demonstrated by the 1999 Seattle WTO protest, the largest American leftist mobilization in decades, which was primarily comprised of “NGOs like the Naderite Public Citizen…Global Exchange; the International Forum on Globalization (IFG)” as well as “anarchist groups, like the Direct Action Network (DAN), The Ruckus Society, and Earth First!” (Henwood 2019). As Vincent Bevin’s latest book If We Burn explains, this lack of large-scale organization coupled with the popularity of anarchist horizontalism meant that when crises did arise, the left was ill-prepared to capitalize on them (Bevins 2024). The financial crash of 2008 and the murder of Michael Brown in 2014 both prompted massive social unrest and waves of radicalization, culminating in the Occupy Wall Street and Ferguson Uprising protest movements that mobilized thousands of people across the country and exposed millions more to anti-capitalist and anti-racist politics. Without any organizational infrastructure or political will to coordinate tactics or develop long-term strategy, however, both of these movements failed to translate their spontaneous popular energy into lasting social power.

Then came Bernie Sanders. Senator Sanders’ 2016 presidential campaign was nothing less than a political earthquake, which shook many pre-existing leftists out of their anti-electoral, disorganized stupor, and awakened millions of regular people to the possibilities of working-class politics. By describing himself as a democratic socialist and running a campaign based on widely popular economic demands, Sanders breathed new life into the floundering American socialist movement, radicalizing a new generation of young people and turning them into trained organizers through his grassroots volunteer structure. Following his defeat to Hillary Clinton in the Democratic primary, Bernie attempted to direct the popular energy generated by his campaign into his new Our Revolution organization, but much of it went to other groups such as the progressive Working Families Party or the openly socialist Democratic Socialists of America, which saw its membership explode over the 10,000 person mark for the first time in its 34-year history (SocDoneLeft 2024). Bernie’s campaign also inspired a wave of young progressives to run for office, including Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (herself a former Bernie campaign organizer) who defeated long-time Democratic incumbent Joe Crowley in 2018. As membership in socialist organizations continued to rise, more and more progressives won elections, and another Bernie presidential campaign loomed on the horizon, the American left circa 2019 seemed poised to enter an era of growing popularity and even mass appeal.

Unfortunately, the limits of this new ‘progressivism’ soon became apparent. Bernie’s 2020 campaign was obliterated by the backroom machinations of the DNC, and instead of funneling the energy generated by the campaign into lasting organizations, “all of the energy, data, and infrastructure of the campaign instantly went up in smoke…leaving little trace behind” (Fong 2022). On Capitol Hill, Ocasio-Cortez and other members of “The Squad” came under attack from the left over their increasingly cozy relationship with the Democratic Party establishment and their “opportunist” positions on a number of issues, particularly the question of Palestinian liberation. Meanwhile, the world kept getting worse: Trump’s election in 2016, the DNC coup to install Biden in the 2020 Democratic primary, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor by police all launched fresh waves of radicalization and discontent across the country. While many of these newly radicalized joined existing large organizations such as DSA, whose membership spiked to nearly 80,000 in 2021, many more did not join any organization at all or turned to much smaller, more radical sects (SocDoneLeft 2024). This leads us to our present condition. While the post-Bernie left is certainly significantly larger, more well-organized and relevant than the pre-Bernie left, it still leaves much to be desired, and in many respects has only gotten worse since 2021. For all our gains, the left remains incredibly fractured, disorganized, and unstrategic, meaning that if we are serious about winning our demands, we must deeply interrogate our current shortcomings and attempt to change course.

Such an interrogation should begin by analyzing the orientation which currently dominates the American left: ultraleftism. The characteristics identified above from Lenin and Camejo’s works provide a useful structure for analyzing ultraleftism, so let’s go through them point by point and see how they apply to our present moment.

I. Ultraleftism primarily develops as a reaction to the limits of center-left politics.

For all the success left-of-center politicians such as Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, and Alexandira Ocasio-Cortez have had in exposing great masses of people to politics outside of the neoliberal mainstream, the clear limits of their ‘progressive’ approach have also radicalized many people towards ultraleftism. Bernie’s failure to win the Democratic nomination twice, along with the inability of “The Squad” to achieve significant victories since being elected to congress, has convinced many people that electoralism is a “dead end” that cannot bring about changes on the scale necessary to challenge capitalism or other systems of oppression. The spread of this anti-electoralism has accelerated since Oct. 7th, as Bernie, AOC, and other center-left politicians’ milquetoast and equivocal responses to Israel’s genocide have only further popularized the notion that electoral politics is just for unprincipled opportunists. As progressive politicians continue to flounder in the face of intensifying crises, disenchanted supporters are turning to more radical options in search of solutions.

II. Ultraleftism inverts center-left thinking without breaking with its fundamental structure of thought.

In seeking to distance themselves from ineffective liberals and opportunist progressives, ultraleftists repudiate many of their positions simply by inverting them: where American liberalism views voting in elections, peaceful protests, and the American-led ‘free world’ as inherently good things, American ultraleftism views them as inherently bad. As stated above, the anti-electoral impulse has become extremely popular within the modern left, and even among those who do recognize the necessity of participating in elections, small, hyper-radical third parties with no existing base of support or mass appeal (such as the Party for Socialism and Liberation, the Green Party, the People’s Party, or the Communist Party USA) are held up as the only ‘legitimate’ forms of electoralism. If for liberals voting represents the highest form of political participation, for ultraleftists it represents the lowest, a kind of elaborate theater meant to enchant and distract regular people from ‘real’ politics. Tactically, ultraleftists dissatisfied with the endless peaceful, non-disruptive marches characteristic of liberalism (such as the Women’s March or corporate Pride Parades) have turned to increasingly minoritarian actions which emphasize disruption over all else. Small teams of dedicated radicals carrying out industrial sabotage, blocking roadways, or even just breaking random windows in a riot are viewed as the most effective means of political expression, for, as the phrase goes, “direct action gets the goods”. The subject where ultraleftism’s mirroring of liberalism is most apparent, however, is international politics. Instead of earnestly breaking with the nation-state centric, elite model of geopolitics embraced by liberalism, ultraleftists simply flip the lists of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ countries in the name of anti-imperialism and refuse to analyze them further. Regardless of the condition of the working class or the level of human rights within a country, ultraleftists will support any government as long as it is even nominally anti-American. While this is most apparent when it comes to those few remaining supposedly ‘communist’ countries like China or North Korea, ultraleftist ‘anti-imperialism’ has also increasingly extended support to even the most reactionary of regimes such as Iran or Russia. Even while this essay was being written, the poster child of American ultraleftism, Calla Walsh, put out a post chiding those criticizing Burkina Faso’s decision to criminalize homosexuality, arguing that such criticisms based on “Western frameworks of ‘LGBTQ+ rights’” are “chauvinism and infantile idealism” (Walsh 2024). Such infantile, uncritical campism, which leads self-proclaimed leftists to defend military juntas banning homosexuality and developmentalist regimes which cause workers to throw themselves from the rooftops of factories, is a clear demonstration of how the ultraleftist orientation flips liberalism on its head without bothering to challenge its core assumptions.

III. Ultraleftism rejects mass organizing in favor of minoritarian strategies that only mobilize the already-radicalized.

While ultraleftism has certain core characteristics, the way these characteristics manifest in a given moment varies based on historical context and individual experience. Hence, while the American ultraleft today is united in their preference for minoritarian, hyper-radical tactics, their reasoning for selecting these tactics is divided between those who openly reject the masses and those who assume the masses are already at their level of radicalization. Just as elite liberals disdainfully view the American working class as hopelessly conservative and stupid, a large subset of ultraleftists view American workers as inherently reactionary ‘labor aristocrats’ too committed to white supremacy and imperialism to ever be organized. Since organizing the first-world masses is a priori impossible for these ultras, they either turn to highly minoritarian acts carried out by tiny sects aimed merely at disrupting the system, or abandon organizing all together in the name of a kind of messianic Third-Worldism. Other ultraleftists, in an attempt to resurrect extinct ideologies like Maoism or Marxism-Leninism, embrace the language of mass action but nonetheless still pursue minoritarian tactics and do not reckon with the real state of the working class. For these ultraleftists, ‘the masses’ are not a concrete group in society that must be met where they’re at, but are rather a rhetorical hammer used to attack opportunists, bureaucrats, or anyone else deemed insufficiently radical. Whether they hate the masses or use them as a discursive prop, however, all modern ultraleftists fail to orient themselves towards the masses or understand their present level of class-consciousness. Ultraleftists revel in the subcultural status afforded by their arcane ideologies and small sectarian communities, always using the most radical (and often the most opaque) language possible to distinguish themselves from ‘normies’. Rather than running campaigns based on widely and deeply felt issues, they shout only the most revolutionary slogans and demands, denigrating anything less as cooptation and compromise. As stated above, ultraleftists prefer small groups carrying out disruptive acts over large campaigns that attempt to meet the masses where they’re at. They favor these small disruptive actions either because they are trying to act without the masses, or because they’re trying to inspire the masses to radical action through a modern propaganda of the deed – in both cases, the actual existing level of class-consciousness among the masses is ignored. By fetishizing direct action over all other tactics, the ultraleftists come to value spectacular physical power (such as the spectacle of physically blocking a roadway, breaking a window, or punching a cop) over structural social power. Valorizing spectacle over substance causes them to further prioritize tactics that allow small groups to create big scenes without actually building much power, such as minority wildcat strikes, occupations of public spaces or buildings by small cadres, and street-fighting with far-right or police forces. The problem with this is not the tactics themselves, but rather the ultraleft insistence that they are the only tactics that can be used. Instead of viewing wildcat strikes or occupations as tools in our tactical toolbox that should be used at specific moments when they are most strategic, alongside other tools like electoralism and unionization, ultraleftists view them as the only valid tools all of the time, leading them to use these tactics in ineffective ways and at unstrategic moments. To the ultraleftist with a direct-action hammer, every problem looks like a nail.

IV. Ultraleftism is a strategic orientation which can manifest as a wide variety of ideologies.

Ultraleftism today is extremely ideologically diverse, manifesting both as an array of revived hyper-specific historical ideologies (e.g. anarcho-syndicalism, Hoxhaism, Maoism, etc.) and as a kind of amorphous, syncretic radicalism that draws on many lineages without defining itself as any one in particular. The first manifestation, revived historical ideologies, is a kind of political necromancy which has become possible in large part thanks to the internet. By providing new radicals with endless Wikipedia articles, Reddit communities, Discord servers, and even historical strategy video games (I’m looking at you, Hearts of Iron IV!), the internet has created a situation where ultraleftists can pick and choose an ideology to adopt like selecting a product from a catalog. Indeed, in their attempt to radically repudiate existing politics, there is perhaps nothing more appealing to ultraleftists than an ideology torn from an entirely different time period. Ripped from their original historical contexts and uncritically applied to our modern conditions, these zombie ideologies shamble on primarily in internecine, arcane social media debates that, much like those who participate in them, have no relation whatsoever to the real world. While the internet creates the possibility of resurrecting hyper-specific ideologies, it also creates the conditions for the spread of amorphous un-specific radicalism. Divorced from any existing organizations or real-life social base, modern online radicals are free to treat ideologies as subcultural aesthetics. Whereas once being a communist or a socialist almost definitionally meant being actively involved in an organization or party, now it merely means that you listen to left-wing podcasts, follow left-wing social media accounts, use left-wing phrases and memes, etc. Defined more by aesthetic than by strategy, this kind of syncretic radicalism seems today to primarily draw on decolonial, third-worldist, and Marxist-Leninist themes, though some strains align themselves more with the anarchist and libertarian socialist lineages. Organizationally, the hyper-specifics tend towards ideologically defined sects like Trotskyists splinters or PSL, while the syncretic radicals tend towards single-issue advocacy groups (if they are involved in any real-world organizing at all). Prior to 2016, most ultraleftists were of the hyper-specific ideology variety, and were typically super-online cranks or aging New-Left boomers still committed to their tiny organizations. Increasingly over the past few years however, as ultraleftism has become more and more prominent within the American left, the amorphous syncretic radicalism characteristic of young, newly-radicalized people has become more dominant. While you’re certain to still find a few newsboy-capped Trotskyists or fire-breathing RevComs milling around the edges of any major leftist event today, the majority of new ultralefts tend to be ideologically undefined and more committed to certain individual issues than any larger organization or party.

The renewed dominance of the ultraleft in America could not have come at a worse time. Between the COVID-19 pandemic, the increasingly certainty of a second Trump term, and the genocide in Gaza, many millions of people have grown increasingly dissatisfied with the status-quo and are have begun searching for real political alternatives. And yet, instead of this growing dissatisfaction and radicalization translating into rising membership in left-wing organizations, more leftists being elected to office, or union density increasing, the left has only become more marginal, ineffective, and disconnected from power. This is because, as Matthew Karp eloquently put it in his recent article for Harper’s Magazine, “the American left has failed to develop a politics capable of winning over the American public” (Karp 2024). Nowhere has this failure, and its deadly consequences, been more evident than in the Palestinian solidarity movement since Oct. 7th. Constituted primarily by an incredibly loose coalition of single-issue anti-Zionist organizations and socialist groups, the Palestinian solidarity movement that has arisen over the past nine months has mostly pursued the tactics of “large demonstrations, in cities, towns, and most notably at the US Capitol”, “more spectacular instances of civil disobedience”, and “student protests, encampments and walkouts” (Mabie 2024). The massive turnout many of these “large demonstrations” have received, alongside the broad popular support for a ceasefire (as of February 2024, around 67% of voters, including 77% of Democrats, support the U.S. calling for a permanent ceasefire in Gaza), indicates that the ground is fertile for a mass-movement against the Israeli genocide of Gaza that could not only win a ceasefire, but also educate millions about the reality of Zionist apartheid in Palestine (Data For Progress 2024). Unfortunately, rather than these large protests being used as a means to organize bigger and bigger groups of people around a popular demand, they have predominantly been used by ultraleftist organizers to “reinforce particular slogans” and “in front of a captive audience, establish the militancy, commitment, and attraction of the primary organizers” (Mabie 2024). The “spectacular instances of civil disobedience” have served a similar purpose, as relatively inconsequential but highly visible acts of disruption (such as blocking a highway, or breaking windows at an arms factory) have been used to demonstrate the militancy and commitment of the perpetrators, not to actually organize the many people needed to really disrupt the system at a large-scale. On campuses, the heroic student encampments only managed to mobilize a relatively small section of the student population (a far cry from the supermajorities that went on strike during Camejo’s time) before being erased by overwhelming police repression, typically without winning any of their demands. Indeed, despite nine continuous months of endless protests, rallies, direct actions, and occupations, the genocide in Gaza continues apace, and we seem no closer to winning a ceasefire – let alone freeing Palestine entirely – than we did at the start.

Given this immense failure to produce results on such a critically important issue, and the widespread powerlessness that such a failure is a symptom of, it should not be surprising to anyone that multiple people have turned to self-immolation in an attempt to stop the genocide. While Aaron Bushnell’s sacrifice is the most well-known case, it should not be forgotten that another protestor set themselves on fire outside of the Israeli consulate in Atlanta a few months prior, though reporting seems to indicate this person did not die (Reuters 2023). While Bushnell and others’ bravery and selflessness should be recognized, it is irresponsible and short-sighted to not also recognize that they should not have felt this was necessary in the first place. That the left is so disempowered and disorganized that two people felt the only way they could achieve a modicum of change was to publicly kill themselves is a horrific and damning indictment of our deep strategic failures. The same can be said of every death in Gaza, where millions of people continue to suffer for our mistakes. All people of consciousness must recognize: we need to do better.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Surpassing ultraleftism is easier said than done. To start with, it is very difficult to convince ultraleftists to change their minds simply by talking to them or debating them. This is because they tend to conflate strategic opinions with moral stances, leading them to view any critiques of their strategies as attacks on their moral characters. The social in-group pressure to appear as radical as possible within many ultraleftist spaces further encourages this inability to take criticism or objectively review strategy, as ideological dogmatism is prioritized over tactical effectiveness. This all means that criticizing ultraleftism or attempting to debate an ultraleftist will likely only make them double-down and dig in their heels, not meaningfully change their minds. Beyond just convincing existing ultraleftists of the error of their ways, efforts must also be made to stymie the flow of new ultraleftists. This requires addressing the source of ultraleftism: center-left opportunism. Since ultraleftism primarily arises as a reaction to opportunism, one cannot be surpassed without also surpassing the other – they are complementary disorders that cannot be dealt with separately. As long as opportunist center-leftism remains prominent among left-wing politicians (such as Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, AOC, etc.), those who rightly become dissatisfied and disenchanted with the limits of that orientation will continue to radicalize into ultraleftists. A real alternative to both liberalism and ultraleftism is needed.

As Lenin and Camejo repeatedly emphasize, mass politics is that real alternative. Rejecting the minoritarian, elitist approach to politics shared by both center-left opportunism and ultraleftism, mass action politics instead orients itself towards the multiracial working class and understands that none of our major demands (from freeing Palestine to ending capitalism) can be achieved without the support of the masses. Both Lenin and Camejo intrinsically understood that organizing the masses is essential to winning power. Lenin wrote that “It is, I think, almost universally realized at present that the Bolsheviks could not have retained power for two and a half months, let alone two and a half years…without the fullest and unreserved support from the entire mass of the working class”; similarly, Camejo remarked “The working class and the oppressed nationalities are mass social layers, and they can only realize their potential power when they organize as a massive social force. The ruling class can deal with any one individual or any small group; it’s only masses that can stand in their way” (Lenin 1920, p. 9; Camejo 1970). When the masses are viewed as the principal agent of social change, “one must not count in thousands, like the propagandist belonging to a small group that has not yet given leadership to the masses; in these circumstances one must count in millions and tens of millions” (Lenin 1920, p. 75). But how do we move tens of millions to action?

We start by running campaigns based around widely and deeply felt issues – “our concept is to unite people in action around the issues on which they’re moving” – since by focusing first on already-popular demands, rather than morally-righteous but unpopular demands, we can mobilize large groups of people and in the process radicalize them to support those currently unpopular demands (Camejo 1970). Camejo explains this radicalization-through-mobilization as follows: “you put people in motion, precisely because when they start to move on any one issue…people begin to question the whole society, and to see the interrelationship between the different issues. In fact, it is the way people radicalize” (ibid). It is key to recognize that the only way to “put people in motion” on a large scale is by appealing to issues they already care about. While a super radical demand like ‘end capitalism’ would likely be relatively unpopular among a union of workers today, a widely and deeply felt stepping-stone demand like ‘raise our wages’ would both move many more people to action and, in the process, expose them to the realities of class struggle and the necessity of broader changes. Unlike the stochastic, individualist radicalization characteristic of ultraleftism, where random people on their own become fed up with center-left opportunism and flip it on its head, this radicalization through popular mobilization is aimed at deliberately radicalizing large groups of people. An illustrative recent example of the power of popular mass demands was Bernie Sanders’ two presidential runs. By eschewing unpopular overly-radical posturing in favor of widely and deeply felt demands like medicare for all and student debt relief, Bernie was able to tap into a broad base of support, organizing hundreds of thousands of volunteers and in the process educating millions of Americans about class struggle and socialist politics. Of course, the success of the mass-action elements of Bernie’s campaigns has been recently overshadowed by his opportunistic loyalty to Genocide Joe and the Democratic Party, but just as Lenin extracted the mass-politics portions of Kautsky’s thought from his ultimate opportunism, so too should we seek to embrace the mass-action elements of Bernie’s campaigns while discarding his opportunism. Indeed, it is only through mass politics that both Bernie’s opportunism and the ultraleftism it has spawned can be surpassed.

With this vision of mass politics in mind, we can begin to imagine a more popular and effective version of the Palestinian solidarity movement. Luckily, we already have some material to draw on: for the many ultraleftist mistakes that have shaped the movement over the past nine months, there have also been a number of nascent mass-action oriented strategies and tactics. Organizing around the already widely popular demand of an immediate ceasefire, activists have started “campaigning for cease-fire resolutions, aimed at any and all institutions, though unions and city councils seem to be the two prominent places”, including “consistent demonstrations targeting politicians’ offices to support a call for cease-fire” (Mabie 2024). The Uncommitted campaign, which organized voters across the country to protest Biden’s support for the genocide by voting uncommitted (or leaving their ballots blank) in Democratic primaries, “has collected union and movement group endorsements on its way to solid performances in a number of states” (ibid). On campuses, while some occupations have been dominated by unelected ‘leaders’ who push for ‘escalation’ over building mass support, others have prioritized internal democracy and used the encampment as a way to organize as many students as possible. At San Francisco State University, student organizers rejected “escalations by small groups, especially with vague demands” in favor of “moving together in the hundreds” through “daily open assemblies”, “standing committees, open to anybody staying or consistently participating at the camp”, “open political discussions”, and “open bargaining” by “elected bargaining reps” (Brown 2024). Rather than maintaining operational security by making “the pivotal decisions in small or even secret groups”, SFSU organizers argued that “our best security is strong politics”, as “If we’re committed to decide democratically and act all together for our shared demands, that’s what keeps us safe” (ibid). Most importantly, “the organizing committee has focused on getting broader layers of students to participate by canvassing campus paths and dorms with demand flyers and invitations to join assemblies, and training new activists to do one-on-one conversations to bring in new classmates” (ibid). Thanks to their democratic, mass-action oriented strategy, the SFSU occupation was actually successful in winning 3 of their 4 demands, including divestment “from companies that fund war or support Israel”, and the organizers view this victory as a stepping-stone to bigger changes: “what we’re working toward now since we’ve gotten this really important first step on our campus is organizing with students on all the CSUs to come together, to the Board of Trustees meetings and make that change on a more systemic level” (Kafton 2024). Finally, and perhaps most significantly, UAW 4811 went on strike across the University of California (UC) system in May to demand that the UC administration stop repressing the free speech of pro-Palestinian students and workers (UAW 4811 2024). Though ultimately paused by a temporary restraining order issued by a reactionary judge, UAW 4811 demonstrated that by appealing their members’ interests – “whatever opinion union members may hold on these root issues, the serious, violent, and unlawful repression faced by our coworkers demands that we stand in solidarity in this moment” – it is possible to mobilize tens of thousands of workers to bring the entire statewide university system to a halt for Palestine (ibid). Rather than launching minoritarian wildcat strikes that are strong on radical rhetoric but weak on real leverage, worker organizers across the country should emulate UAW 4811’s explicitly mass action strategy which prioritizes (super) majority action, deep organizing, and worker-led democracy (Union MADE 2024).

Of course, creating a mass-oriented movement that uses the popular demand of an immediate ceasefire to move people to action and radicalize them in the process requires both a significant realignment of the contemporary American left’s strategic outlook and a unification of our disparate organizations and communities. This promises to be a very fraught and time-consuming process, and yet, if we are serious about winning our demands, it is a process we cannot avoid. We owe it to the people of Palestine to be ruthlessly effective, and to eschew self-aggrandizing radical posturing in favor of actually building the power required to free Palestine. In fact, as workers living in the heart of the imperial core, we owe it to the whole world and ourselves to do better. We must build a mass socialist movement that has not hundreds or thousands but millions of members actively participating in a democratic, unified party that can really win power. Fortunately, just as the already-existing Palestinian solidarity movement contains within it the nascent seeds of mass action, so too does the current socialist left harbor mass potential in the form of the largest socialist organization in the country: the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA). Though DSA is far from a perfect organization – it has its own opportunist and ultraleft tendencies, for one – it is clearly far and away the best current option with the most potential for the future. With membership easily four times as large as the next biggest socialist organization, and a member-led democratic structure that allows for ideological diversity, DSA is perfectly positioned to become the organizational heart of the American left (SocDoneLeft 2024). For DSA to accomplish its world-historical mission, however, the opportunist and ultraleftist tendencies both within DSA and throughout the broader left must be overcome by effective mass organizing. Only by expanding beyond our radical bubbles and really moving millions to action can we “not only play, but make, a revolution” (Camejo 1970).

Works Cited

Bevins, Vincent. Interview with Daniel Denvir. 2024. “Why a Decade of Protests Didn’t Lead to Revolution”. Jacobin. https://jacobin.com/2024/01/vincent-bevins-interview-mass-protests-2010s-arab-spring-euromaidan

Brown, Keith Brower. 2024. “At San Francisco State, a Democratic Movement for Palestine”. Jacobin. https://jacobin.com/2024/05/san-francisco-state-student-protest-palestine

Camejo, Peter. 1970. “Liberalism, Ultraleftism or Mass Action”. https://www.marxists.org/archive/camejo/1970/ultraleftismormassaction.htm

Data For Progress. 2024. “Voters Support the U.S. Calling for Permanent Ceasefire in Gaza and Conditioning Military Aid to Israel”. https://www.dataforprogress.org/blog/2024/2/27/voters-support-the-us-calling-for-permanent-ceasefire-in-gaza-and-conditioning-military-aid-to-israel#:~:text=Around%20two%2Dthirds%20of%20voters,escalation%20of%20violence%20in%20Gaza

Early, Steve. 2020. “Fifty Years Ago This Spring, Millions of Students Struck to End the War in Vietnam”. Jacobin. https://jacobin.com/2020/04/kent-state-shooting-vietnam-war-protest-student-organizing

Fong, Benjamin Y. 2022. “If Bernie Runs in 2024, His Campaign Should Build a Left Political Organization”. Jacobin. https://jacobin.com/2022/08/bernie-sanders-2024-campaign-left-political-organization

Henwood, Doug. 2019. “Twenty Years After We Shut Down the WTO, the Left Is Finally Resurgent”. Jacobin. https://jacobin.com/2019/11/world-trade-organization-seattle-protests

Hoffrogge, Ralf. 2015. Working-Class Politics in the German Revolution: Richard Muller, the Revolutionary Shop Stewards, and the Origins of the Council Movement. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

Kafton, Christien. 2024. “SFSU protesters break down encampment after reaching agreement”. KTVU Fox 2. https://www.ktvu.com/news/sfsu-protesters-breaking-down-encampment-after-reaching-agreement

Karp, Matthew. 2024. “Blank Ballot”. Harper’s Magazine. https://harpers.org/archive/2024/08/blank-ballot-matthew-karp-easy-chair/

Lenin, V.I. 1920. ‘Left-Wing’ Communism: An Infantile Disorder. New York: International Publishers.

Mabie, Ben. 2024. “Newsletter #95: Gaza and US politics”. The Dig. https://thedigradio.com/newsletter95

Miller, Amanda. 2020. “May 1970 Student Antiwar Strikes”. University of Washington, Mapping American Social Movements Project. https://depts.washington.edu/moves/antiwar_may1970.shtml

Reuters. 2023. “Protester self-immolates outside Israeli consulate in Atlanta”. https://www.reuters.com/world/us/protester-self-immolates-outside-israeli-consulate-atlanta-2023-12-01/

SocDoneLeft. 2024. “MemLeftOrg Dataset: Members of leftist organizations, 1848-2024”. https://socdoneleft.substack.com/p/memleftorg-dataset-members-of-leftist

UAW 4811. 2024. “UAW 4811 ULP STRIKE FAQ”. https://www.uaw4811.org/sav-faq

Union MADE. 2024. “Our Platform – Union MADE”. https://www.union-made.org/our-platform

Walsh, Calla. @CallaWalsh on X (formerly known as Twitter). https://twitter.com/CallaWalsh/status/1812136229216850333

Young, Ethan. 2018. “Everything You Wanted to Ask About Sects … But Were Afraid to Know”. Jacobin. https://jacobin.com/2018/07/new-communist-movement-revolution-sds-maoism

this sucks ass